While some students enter college with the advantage of a college savings account funded by their families and/or financial aid in the form of scholarships and grants—others are reliant upon loans to accomplish their educational goals. For some (such as myself) who have had to use loans to fund their degrees (in my case, upwards of $200K + for graduate studies), demographic data shows that college loan debt is more detrimental in certain communities than others, specifically in the Black or African American community. Concerning the student loan debt I’ve acquired, I can honestly say, “the struggle is real!”

Sandy Baum, Nonresident Senior Fellow for the Urban Institute, points out that African American students are more likely to borrow than students from other racial and ethnic groups pursuing degrees in similar fields. African Americans are also more likely to borrow larger amounts of money and are also not as successful in repaying their loans, thereby making them more likely to default. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), an estimated 86.8% of African American students borrow federal student loans to attend a four-year public college, compared to 59.9% of White students. Data released by the U.S. Department of Education in 2017 shows that nearly 50% (e.g., 1 out of every 2) of Black or African American borrowers who entered college for the first time in the 2003-04 academic year went into default on their student loans within 12 years. Further data showed that the numbers did not improve almost a decade later. For example, African Americans who borrowed money for college in the 2011-12 academic year are still facing high default rates as those just ten years prior.

In a more limited comparison of default rates, data sets show that six years after Black students entered college, who borrowed during their freshman year, there were minimal changes across cohorts. According to the Brookings Institute, Black borrowers are more than three times as likely to default within four years of graduation as White borrowers (7.6 percent versus 2.4 percent). Without question, loan default is a crisis among Black borrowers, and it has persisted, even with the multiple loan repayment options created by federal policymakers to assist those struggling with debt.

Featured articles

Caring for Natural Hair: Tips for Queens with Tight Curls & Coils

supermodelsociety.org https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png

1809

668

https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Hair-Care-article-pic-1-950x1024.jpg

800

862

https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png

1809

668

https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Hair-Care-article-pic-1-950x1024.jpg

800

862

Fragrance Guide: Picking the Right Scent For You

supermodelsociety.org <img src="https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png" alt="Fragrance Guide: Picking the Right Scent For You"/> https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png 1809 668 https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Fragrance-1024x683.jpeg 800 534Understanding Blockchain Technology & Its Investment Potential

supermodelsociety.org <img src="https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png" alt="Understanding Blockchain Technology & Its Investment Potential"/> https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/cropped-Updated-Logo.png 1809 668 https://supermodelsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/blockchain2-1024x512.jpeg 800 400With rising tuition costs outpacing inflation and wage growth, many students are struggling to afford college. In fact, about 44 million Americans owe over $1.48 trillion in student loan debt. What’s more, the student loan debt crisis prevents millions of young Americans from homeownership, starting families, saving for retirement, and generating wealth. These deleterious effects are even greater for African Americans as they are held back more by student loan debt than other groups. For example, Black students are 20 percent more likely than white students to need federal student loans for college. On average, as a partial consequence, they graduate with $7,400 more in student loan debt in contrast to their White counterparts—essentially, $23,400 versus $16,000, as noted by the Brookings Institute.

Earning a college degree is just the beginning of the student loan debt disparity for many African Americans. Black college graduates entering the workforce with recently earned degrees are not only faced with the obstacles of securing a job in their actual field of study, but that is often coupled with a loan repayment that starts six months after graduation. When looking at the next few years after earning a four-year degree, the Black-White debt gap more than triples to a whopping $25,000. As pointed out by the Brookings Institute, differences in interest accrual and graduate school borrowing lead to Black graduates holding nearly $53,000 in student loan debt four years after graduation, almost twice as much as their White counterparts.

As the only sure way to get rid of debt is to pay it off, when looking at student loan debt pay-down rates between Blacks and Whites, White borrowers pay down their education debt faster at a rate of 10% a year. In contrast, Black borrowers pay down student loan debt at a rate of 4% annually. Not surprisingly, the longer it takes a borrower to pay down debt, the more interest they will pay—thereby increasing their total debt.

What are the major contributors to the student loan debt crisis that are distinctly stratified across racial lines? Given the United States’ pernicious persistence in systemic racism—which is very much evidenced in the labor force—there is no surprise that more often than not, Black students are at a financial disadvantage when it comes to higher education debt outcomes. This disadvantage is four centuries old—a disadvantage which started long before it was time for them to enroll in college. Mark Huelsman, Senior Policy Analyst for Demos, stated, “We cannot think of student loan debt in isolation from other areas of our economy…long-standing racism in the labor market has resulted in a country where Black families with college degrees have lower average net worth than White families with a high school education or less.” In the world of economics, debt (including student loan “good” debt) lowers a person’s net worth.

In addition to racism in the labor market, the cost to attend college is increasing—outpacing the rate of inflation and growth in family income. Further, need-based grant aid, designed to defray costs for low-income students, has also dwindled as a percentage of college costs. Needless to say, this means that the students who already have the most difficulties financing their education—namely, lower-income African Americans and Latinos—end up borrowing the most, and sadly, defaulting the most. Huelsman notes, “low-income graduates (those who received a Pell Grant while in school) borrow at far higher rates—and in higher amounts—than their middle- and upper-income counterparts at both two- and four-year institutions, regardless of the type of institution attended, and despite receiving thousands of dollars in grant aid. Black students also borrow at much higher rates, and in higher amounts, to receive the same degrees as their White counterparts.” In addition to that, African American college graduates often make less money than both Whites with a college degree or Whites with only a high school diploma.

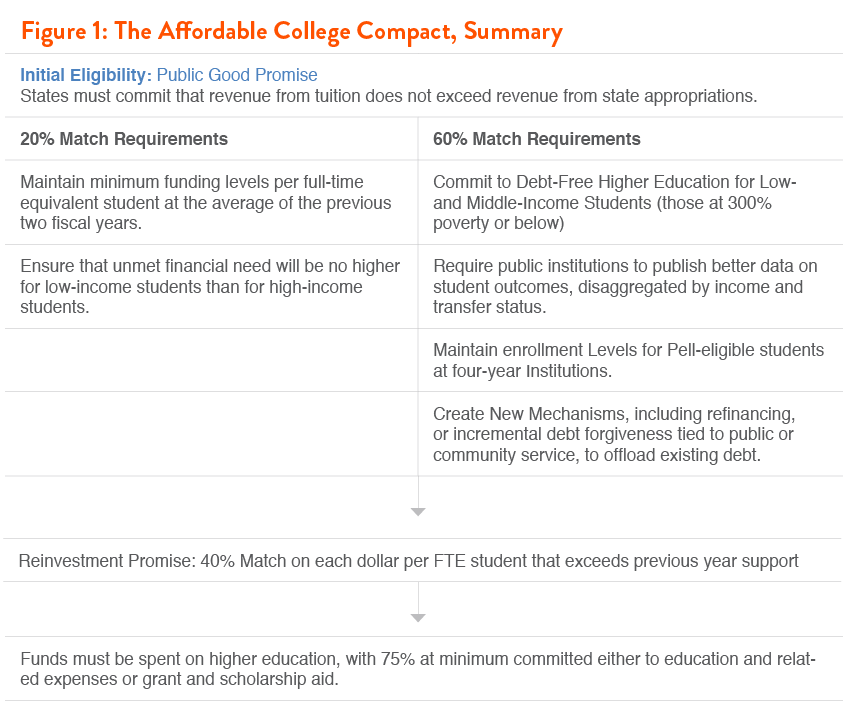

When looking at the data, this begs the question, what can be done to help alleviate these disparities? To begin, alternatives to student borrowing need to be explored. For example, policy recommendations have been proposed, such as a call for an increase in need-based grant opportunities. In one such policy recommendation, the 2014 Affordable College Compact by Demos, Huelsman notes that there should be a “federal-state partnership that would allow the federal government to use its leverage to encourage states to increase state spending, and develop policies and plans to ensure the majority of poor-, working-, and middle class-students can attend college without incurring debt or financial hardship.” See Figure 1 below of a summary of recommendations from the Affordable College Compact:

In 2012, Demos also developed the Contract for College. As noted in the policy design, existing strands of federal financial aid (e.g., grants, loans, and work-study) would be unified into a coherent, guaranteed financial aid package for students. Further, grants would make up the bulk of aid for students from low to middle-income families.

In addition to policy implications, there are also things families can do to address this issue. For example, having a mindset to teach African American children the value and importance of saving and investing “early” is critical. Providing children with the opportunity to be immersed in “liberation education” – learning how to start businesses, investing, and purchasing real estate (all of which are proven pillars of wealth) are all practices that can work in a young person’s favor (economically speaking), BEFORE going to college. As this type of “re-educating” falls out of the purview of standard K-12 education, Black parents would do well to supplement their children’s education by seeking out resources that teach their children these powerful wealth-building strategies. One such resource is the Black Millionaires of Tomorrow program by the Black Business School–an educational institution founded by Finance Professor and Leading Economist, Dr. Boyce Watkins. While all are welcome to take courses, the Black Business School was specifically established for the purposes of providing strong business education for Black people.

In closing, there is no question that a college degree and beyond has both social, political, and economic capital. However, as a collective, we as African Americans would do well to better prepare for the financial responsibilities that come with having a degree. Being informed and making our voices heard by exercising our civic rights to support governmental policies aimed toward making college more affordable is one way to do this. More importantly, in the comfort of our homes (and with technology at our fingertips), we should empower ourselves with educational resources and tools designed for our community in mind, that builds generational wealth.

Comments are closed